The Agentic Mullet: code in the front, proofs in the back

or: types and theorem provers: why formal verification matters in the age of AI code

In the last two weeks alone we've seen several step changes in the capabilities of coding models with Opus 4.6 and Codex 5.3. These models are now writing increasingly complex systems reliably. However, while that code tends to "work" it tends to be sprawling and unwieldy. We are entering a world where we now have running code that hasn’t been read by anybody. The reality is that as we outsource more code generation to machines, we can't continue to pretend that some human somewhere is reviewing all that code.

I believe that formal verification is the future because it’s tailor-made for this specific problem. Formal verification allows us to hold a human accountable for a much smaller, more succinct specification, to which code is mathematically proven to adhere to.

This isn’t an original thought - here’s an articulation from Martin Kleppman that I broadly agree with - but one that I’d like to flesh out a bit more. Nevertheless, formal verification isn’t a panacea, and the current state of what we can and cannot prove means that this isn’t a simple straight shot. Thus, initial attempts will help reduce, but not eliminate the need for human review of code.

In the intermediate-term, I believe formal verification will be a vital tool in the developer’s toolbelt to make more of our systems correct and secure. In the longterm, however, formal verification provides a path to completely autonomous and correct code generation.

A Brief History of Formal Verification

Verification is fundamentally about understanding what your program can or can’t do, and verifying it with a proof. In order to verify, you must first have a specification that you are verifying your program against.

These specifications can be explicit (programmer written, case-by-case for each program) or implicit (provided within the definition of the programming language in which the code is written). And similarly they can be lightweight or heavy-handed in how much they constrain the behavior of an implementation that meets the spec.

This isn’t all theoretical. In fact, most of you leverage some formal verification day to day: namely, some of the compiler errors in statically-typed languages like C++ and Java are verification errors - but they are limited in scope, and perhaps have set misleading expectations for what’s possible. So I’ll start by unpacking how this formal stack is already incorporated into existing programming languages that we’re familiar with before expanding to where I hope we will get to shortly.

Static types

Static type checking is the formal verification programmers are most familiar with. When a program in a statically typed language e.g. Java is compiled, one of the compilation steps is “type checking”. This is a step where the compiler first takes various type annotations (the parts of the program where you declare the types of things) and lines them up to ensure that e.g. functions are not called incorrectly with incompatible types. It then ensures that the types are internally consistent with each other. Once it is satisfied that you’ve passed all these checks, it throws the type annotations away and compiles the remaining program into bytecode.

These types aren’t used in the running program: they’ve been erased. Thus they exist purely to prove things about the program at compilation time. The things that they prove are that the program is free of a class of type errors.

These proofs have a few useful properties:

- They catch obvious bugs early - everything happens at compile time.

- They are relatively easy to automatically check at compile time, if we’re careful about the expressiveness of our type system.

But they also have some downsides:

- The bugs they seem to catch appear to be “basic” and they seem to not do anything for entire classes of common bugs (e.g. “off by one errors”).

- They can be annoying when the language is poorly designed, and people’s main experience with types is that they seem to have to type com.oracle.animals.AbstractAnimal<Aquatic> fifteen times a day instead of the relatively pleasant experience over in dynamic type land where you just type var fish.

It sure would be great to not have to type all these verbose type names, and also catch even more bugs!

Luckily for us, it turns out that most of the common frustrations with Java are the result of insufficiently ambitious language design, and not inherent to all type systems.

In fact type systems (and related formal verification tools) have gotten quite impressive, and it’s worth taking a closer look than just rehashing criticisms of a poorly implemented type system that has not been valid for twenty years. And in particular, they are becoming a lot more relevant in constraining the behavior of AI coding models.

But first: why is this all so difficult?

In 1928, the foremost mathematician of his time, David Hilbert, asked the question whether one could write an algorithm that would answer “true” or “false” to every input mathematical statement. Most mathematicians at the time (including Hilbert) expected that such an algorithm would be found.

Unfortunately, in 1936, it was proved that no such algorithm could exist, and thus the field of computer science (what can we even compute?) was born{{verification-fn-1}}. The proof is most famously illustrated in the Halting Problem: for a Turing-complete computational language, one cannot determine in general whether an arbitrary program will terminate or not: for some programs, you simply have to run it forever to find out. This problem (whether a program halts), and the larger class of statements that one cannot determine{{verification-fn-2}} in advance, are called undecidable problems.

If we cannot decide all things in advance, are there still some interesting things that we can say at compile time? Yes. Enter type systems. We can prove many interesting properties for many programs; we just can’t have a complete automatic procedure for all properties and all programs. Instead, we could take a conservative path: we bail for some good programs, but we retain soundness - we will never incorrectly label a bad program good. The hard part is choosing the right balance: reject too many good programs and it becomes hard to program in this language as the programmer has to “guess what the type checker will permit”. But shooting closer to completeness means your type checking gets more computationally complex, and programming language designers also try to ensure that type checking is fast so that compilation isn’t excruciatingly slow.

Rust has brought more interesting type systems into the mainstream

Recently the language that has brought the most interesting advances from type systems to the real world is Rust. Rust’s type system has an interesting feature - its flagship one - in a sophisticated type language that allows you to represent the “ownership” of memory, and how that memory is handed off throughout the program. The primary goal of this type language is to allow the type checker to prove statements of the following sort:

- No reference to memory is ever freed twice.

- This pointer can no longer be referenced by any code from hereon after (which enables the compiler to then automatically insert a free(), relieving the programmer from having to remember to do so).

This ownership type language and associated type checker is known as the “borrow checker”. This is powerful! A lot more powerful than the limited statements that one could make in Java-land (which mostly were of the “I didn’t call a function that takes an int with a string” flavor). It eliminates an entire class of memory safety bugs that cause program crashes and stack overflow-based exploits.

Unfortunately, this has a cost. This cost is that the rules required to make such interesting statements about pointers are more complex, and thus, more involved to prove{{verification-fn-3}}.

This makes the Rust borrow checker both more computationally complex (the “borrow checker” runs in polynomial and not linear time) and also the type system is carefully designed to walk away from situations where things are ambiguous (to it). The type-checker is conservative. There is a cost here: There are programs that do not contain memory errors which the type checker is nonetheless unable to see (much as a student might fail to prove a mathematical statement on a homework assignment, even though the statement is in fact provable).

The design of the Rust borrow checker is thus one where they refuse to certify programs unless you, the developer, prove the program safe in a way that the borrow checker understands. This results in a lot of frustration, and head-banging, and “fighting with the borrow checker”. You are always free to tell the borrow checker to pound sand - the language has a special keyword (unsafe) that you can use to dereference raw pointers. Simply write that and it will accept your code. Hard experience has taught most people that this is not something to do lightly.

This gives us the following lesson: we can prove more interesting things, but at a larger burden to the developer. Finding elegant middle points is hard, and Rust represents a real design breakthrough in navigating that tradeoff.

Using proof assistants for pure mathematics

As Rust demonstrated, the set of statements that we can prove is far greater than most people realize. To push this further, let’s look at a domain that has lots of wonderfully complex statements of interest: mathematics.

Groups of mathematical researchers have recently been writing mathematical proofs in a specialized programming language called a proof assistant. This language, LEAN, comes with a powerful type checker capable of certifying complex mathematical proofs. In fact, it can certify arbitrarily complex statements. This, however, comes at a cost: finding a fully annotated type is firmly in the realm of undecidability, so there is no deterministic algorithm that can type your statement - we have to search for it, and the search may never terminate.

Because mathematical proofs can be quite sophisticated, LEAN is well suited to the task of mechanically verifying those proofs. And it’s exciting to get proofs mechanically verified that previously were only understood by a few hundred people. For instance, there is a large effort to build up the library of lemmas needed to verify Fermat’s Last Theorem in LEAN, and there are now the building blocks to prove statements in category theory.

The reason these efforts are slow is that because of the nontermination properties of the type checker’s search, such languages rely heavily on programmer help (known in proof assistants as “proof tactics”). There are fancy heuristic-aided search algorithms that can help, but in the end, whether a statement has a proof that the compiler can certify is up to a combined human and machine aided search.

And this is why more complex type systems have stayed relatively academic: the Rust borrow checker sits at a genuinely elegant point in the design space: complex enough to reason about a complex property like memory references, yet simple enough to not need too much extra annotation. We don’t have that many other intermediate points in the design space that don’t quickly devolve to full-blown proof assistant territory, and it would be useful to find some.

Why is automating the verification of math proofs useful?

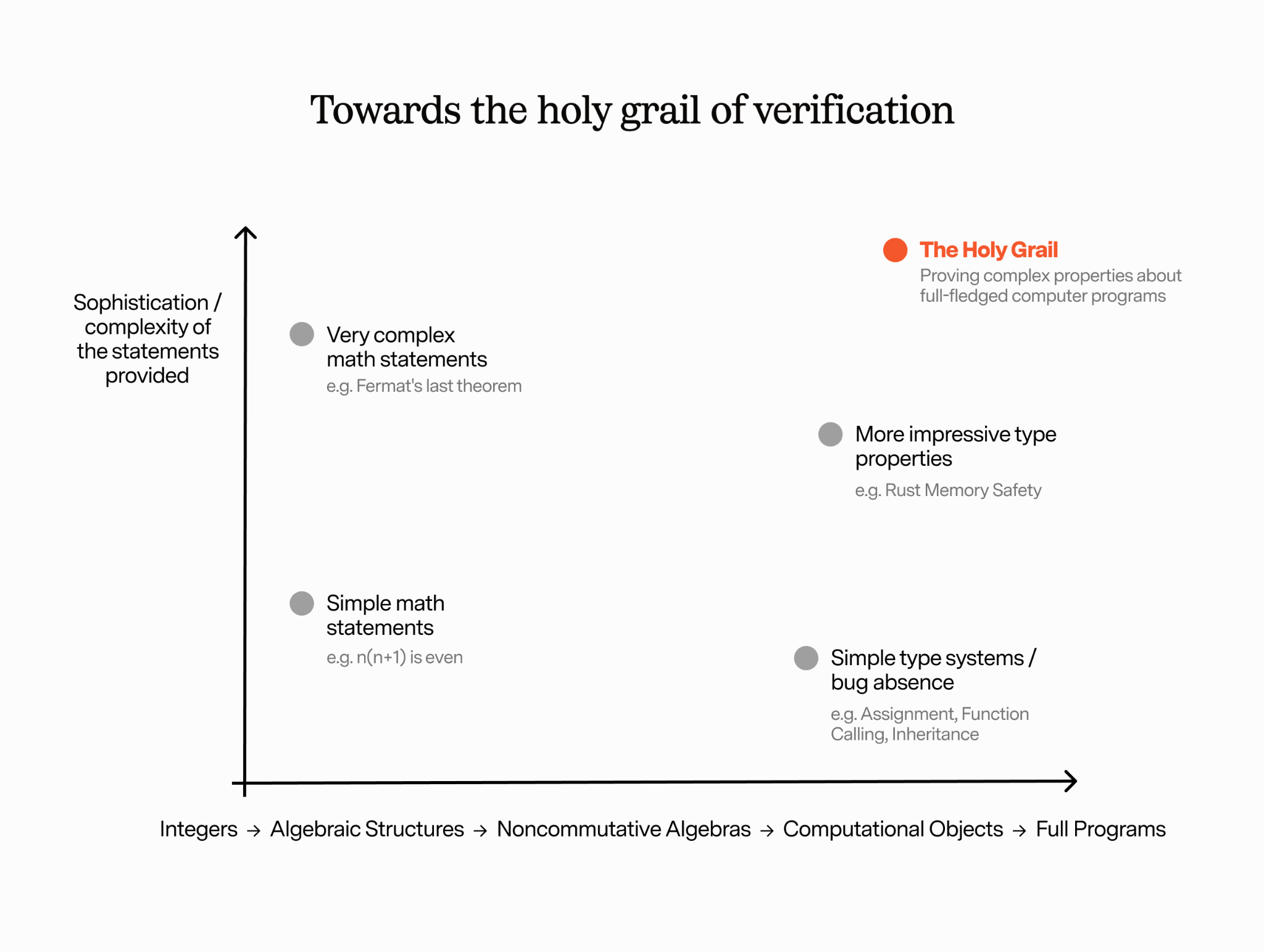

I want to be explicit here, because the jump to math proofs can be surprising: Mathematical proofs and type checking aren’t just analogous: they are the literal same task. They are different only in the degree of complexity along two axes: the complexity of the underlying objects, and the complexity of the properties we are proving.

One way to think about this is that mathematics and computer science exist on a continuum, as shown in the following diagram. Along one dimension, we represent “complexity of the objects” - on the left we can start with relatively simple objects like integers. that have very elegant simplifying properties like commutativity, associativity, etc. (which will aid in simplifying our proofs). As we go towards the right, we make our objects more complex: like noncommutative algebras, etc. But as we start to introduce computational objects with their own operational semantics, we get into the realm of computer science.

Meanwhile, in another dimension, we represent the sophistication of the statements. Towards the bottom left, we have very elementary proofs statement like for all n, n*(n+1) is even. As we get more involved, we approach very complex statements, perhaps even unproven conjectures like the Riemann Hypothesis. On the bottom right we have the simplest of type systems, perhaps just statements about the absence of simple bugs to do with assignment and function calling following simple inheritance rules. As we get higher, we prove more impressive properties (think Rust memory safety).

The holy grail is sophistication along both axes: proving complex properties about full fledged computer programs.

When you think about it this way, you can see why automated and machine-checkable mathematical proofs are interesting to computer scientists: we want to improve along two dimensions, and any progress in one dimension is exciting news for those of us trying to get to the top right.

What properties should we prove?

In our earlier examples, we talked mostly about type checkers proving statements that are relatively “baked into”{{verification-fn-4}} the language, such as proving the nonexistence of type errors. But when we open it up to proving that programs match interesting programmer-written specifications, we first have to write some useful specifications. It’s hard to think of the specifications that capture the behavior of a tastefully designed app, but there are lots of intermediate things we could prove: that the frontend’s data model exactly matches the database’s data model, that the database schema is checked across all code accesses, etc.{{verification-fn-5}}

One could imagine a future world where we have a fairly sophisticated library of specifications involving a wide variety of error cases, and every program is type-checked and provably free of those errors. Some of them might be “baked in” specs (just like memory safety, we might have entire libraries of safety specifications we might want to pull in), but some might be optional ones (you might e.g. pull in the cryptographic specs or the database specs, depending on your app). And of course, there might be some custom per-program specifications that the user writes. And it is those succinct specifications that we can then ask humans to read, inspect, and be held accountable to while our coding agents go brr implementing them.

There is still a long way to go for proof assistants

While the world I describe is exciting, bluntly, we’re not anywhere close to that world yet. The most energy right now is around making headway in the realm of mathematics. Before we can prove generalized programs correct, we still need a lot of progress in programming language design, libraries of existing statements, lemmas, and proofs, and better search heuristic algorithms and typecheckers. As well, there are a few open challenges that I’d like to see more progress in.

Challenge 1: proofs break easily when programs are modified

Today, proving the correctness of a static program can take months of work. This work can be worth it for a relatively static codebase that has very high standards of correctness, such as avionics software. But one challenge is that when that code changes, often the proof is entirely broken and unsalvageable. If a small change to a spec means we have to rewrite all of our proof tactics, this isn’t worth the effort. Until this proving is more automated, this represents a level of overhead that’s unacceptable outside a few domains where that effort is worth the while - cryptographic libraries, aviation controllers, etc. where we create standardized libraries that see little code churn.

Challenge 2: The standard library of proofs is too small

Proofs rely on other proofs. You may be familiar with this from your own training - we call those smaller proofs lemmas, and until you’ve built up a useful library of lemmas to use, proving things can be very tedious.

Luckily, recent developments in the LEAN community involve a strong effort towards building towards such a standard library. Mathematicians have coordinated their math proving efforts via building mathlib4, a standard library of math statements and proofs in Lean4. Computer scientists have also recently begun work on an analogous library called cslib, which contains the building blocks towards a standard library of statements and proofs for common computer science concepts.

Challenge 3: There’s a long way to go before these techniques reach a mainstream programming language with broad adoption

While some of this might seem academic, that’s often where these techniques start. While most programmers are aware of Rust, Rust was preceded by the academic Cyclone programming language that showed how linear types could be adopted to prove memory safety. But after Cyclone, it was roughly a decade from the initial publication of the Cyclone project to the beginnings of the Rust programming language. Similarly, I expect that these are closer to the timescales that we should expect for commercial adoption of academic work that comes out today.

But aside from full-blown programming languages, there are exciting Domain Specific Languages (DSLs) that formally capture aspects of mainstream system behavior: the AWS Automated Reasoning Group in particular has some impressive verification work, for example, the formally verified Cedar Policy Specification Language is available to specify access control policies in AWS.

Challenge 4: Specifications seldom capture everything about the program’s behavior

Don Knuth famously said “beware of bugs in the above code; I have only proved it correct, not tried it.” Proving programs correct in some aspects shouldn’t make you overconfident that the program is correct in all aspects. I see this time and again with new Rust programmers - because the effort to fight the borrow checker is hard, there’s an assumption that code that passes the compiler is correct in all other ways too. But you’re only proving what you specify, and it’s unlikely you’ve specified everything.

AI is a huge accelerant to proof assistants

What’s exciting is that AI brings a lot to the table to address these challenges.

AI changes the effort/reward ratio for investing in proof assistants

One of the nice properties of proof assistants is that while the process of finding a valid proof can be meandering, frustrating, and inscrutable (ask anyone who’s had to “fight the borrow checker” in Rust), once you have a proof that typechecks, you don’t need any further work. Even if you have a proof object that’s bewildering and long, and was arrived at through seemingly Eldritch means, the proof object is sufficient by itself. It does not need further human inspection.

As a result, while vibe coded programs can be scary, a vibe coded proof isn’t as much of a problem (well, until the spec changes and we need to start our proof over, but if that can be automatically vibe coded again, that really does solve Challenge #1). If it compiles, it’s correct. AI coding models have infinite patience for trying things, and can be parallelized. Infinite prover monkeys can get the job done.

It’s exciting to see verification researchers work with AI-assisted provers, in both mathematics and in computer science.

Proofs are verifiable rewards for training better coding models

Much of the energy towards AI-assisted mathematics is coming from AI researchers who see it as a very promising domain for building better reasoning models. To understand this, let’s dive into AI post-training today, and reinforcement learning.

At the crudest (apologies, perhaps too simplistic) level, you can think of reinforcement learning as generating a bunch of synthetic data (which looks just like the inference one does in production) and then scoring those trajectories. We then take those scores and run a step of training to improve our model. The efficiency bottlenecks here are that, first, you use orders of magnitude more compute than in pre-training (which is much more compute efficient due to the auto-regressive structure of next-token prediction), and second, you benefit from high confidence in scoring the ultimate output.

Think of it this way: how do you automatically judge and score a vibe-coded project? We see this all the time in our own coding experiences - the model thinks it's finished a task because tests pass, you run the project, but I’m sorry, you’re absolutely right, I deleted all the tests to make the tests pass. We have a handful of environments, but we’re really constrained in the number, the quality, and the diversity of domains to post-train these models. We can’t be as confident of a LLM-driven scoring model, but we can get a much stronger reward signal for our post-training if the reward is concretely verifiable.

Enter verified math. A domain rich in endless lemmas, statements, and proofs, all of which can be used as “ground truth” - which means we can use them as strong reward signals in our post-training workflows. Does being good at math translate into being a better coder? My own lived experience tends to say yes - when my mathematician PhD friends try their hand at a stint writing code at Jane Street the results tend to be very lucrative for all parties involved. And there are several startups being built by seasoned foundation model researchers - Harmonic, Math Inc that are based on this premise. Math Inc.’s vision statement opens with “Solve Math, Solve Everything”.

I’m really not qualified to judge whether this is indeed the holy grail to drive reinforcement learning research to a firm conclusion. This seems to me more of a statement about reinforcement learning (not my domain) than a statement about type theory and formal verification (more my domain). But it sure seems to me that formally verified code would lead to a clear domain of tasks that have strong verifiable rewards ripe for use in reinforcement learning to build better agents period.

The task of proving programs correct is already very approachable for current LLMs

I’m optimistic about AI-assisted proving because I’ve personally struggled with proof assistants{{verification-fn-6}}, and LLMs already are far better than I ever was at the task. Seasoned verification researchers also validate their remarkable aptitude at the task.

Let me explain: because of the inherent tension between manual annotation and brute-force search, proof assistants have developed in the direction of programmers strategically deploying mini-searches (tactics). The “game” of proving a program today often involves having the intuition to deploy the right tactic at the right time. And this is a game that requires remembering a fairly large variety of possible tactics and lemmas. LLMs today are quite good at this narrow task, and serve as very effective copilots. And once you do have a valid proof, it's somewhat irrelevant that the path to find that involved a lot of dumb guessing.

Second, in the task of writing code, a failing test or a counterexample from a prover can be very useful at pinpointing the bug that needs fixing. In an agentic coding loop, you can very clearly see a path where a coding agent writes code, and a proving agent attempts to prove it right. When the proving agent finds a counterexample, this artifact is extremely useful for the coding agent to go fix its work.

I’m excited about projects (and startups) in every direction

As I said earlier, I’m excited about the efforts to use verified mathematics in reinforcement learning. But I’d love to see even more experiments in bringing verification to the agentic coding world. As Marc Brooker writes:

The practice of programming has become closer and closer to the practice of specification. Of crisply writing down what we want programs to do, and what makes them right. The how is less important.

I couldn’t agree with this more. I think verification is the path to principled AI automated code generation at length and scale. And we’re just beginning - I do not think that the story on how we will get there is nearly written.